The struggle for art

At Art Basel, sociologists have been investigating how the booming art market is turning the art world upside-down – and at the same time sparking off a competition for social power. By Daniel Di Falco

Damien Hirst? Yes, him – the English superstar artist. In 2007 he studded a skull with diamonds and called it ‘For the Love of God’. It is said to have cost 14 million pounds to make and was offered on the market for 50 million. But no one wanted to buy it. And in fact, it was precisely this point that made it a success for Hirst – for he was offering the buyer something that actually possessed an intrinsic value, and in the process he quite wilfully drove all the magic out of art.

When a car mechanic draws up an invoice, he lists the cost of his materials and that of his work time. Art, on the other hand, is precious because it is far removed from any such profanely mercantile criteria. Expenses are indeed incurred in the making of it, but this has no real impact on the actual value of the artwork itself.

Franz Schultheis, a sociologist at the University of St. Gallen, has also written about the magic of art and its demystification. But the case of Hirst is of mere anecdotal value compared to the findings of his research group. For over two decades now, the art market has been veritably erupting, says Schultheis, and it is endangering “the traditional institutions of the art world”. Collectors, dealers, exhibitors and agents have until now guaranteed the ‘charismatic impact’ of their commodities precisely by means of a consensus on not referring to them publically as ‘commodities’.

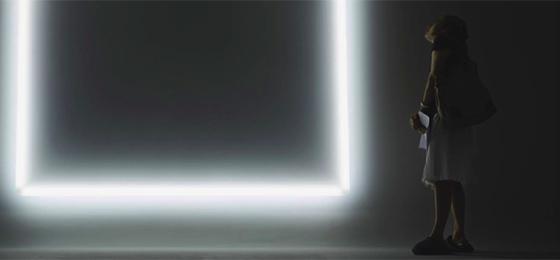

The face of capital

But the sociologists have observed just how difficult it has become to maintain that consensus. For the past three years they have been engaging in fieldwork at Art Basel – it is at this trade fair that they have seen the ‘mercantile character’ of art show its face more openly than anywhere else. And this has also brought out into the open the fundamental contradiction that has dominated the whole art world since Édouard Manet’s club of Impressionist artists in the late 19th century. Their declared belief was adopted as the prime ethos of art as a whole: that art exists in a quite separate sphere of its own, standing apart from all laws of economics and society.

At Art Basel, however, capital certainly shows its face. There we find champagne stalls, sponsors’ events, and all the feverish excitement of making a sale. The researchers have been documenting the hype and the bustle at this ‘carnival’ of art with the meticulousness of ethnographers. And they’ve been investigating its house rules with equal rigour. The VIPs are sorted into different classes and treated according to their economic and social clout; the most potent galleries get the best locations at the fair; and even the art itself is carefully calibrated. What you see most is what sells the best.

There has long been an economics of art. But in years gone by, says Schultheis, it was easier to maintain a ‘collective pretence’. Claims about having a ‘passion for art’ were used as a fig leaf to hide the close relationship between art and capital. In Basel, however, business is centre stage, and when the sociologists start asking questions of the participants, an immense feeling of unease bubbles up. The gallery owners are unhappy because they’ve been displaced by the big auction houses; the collectors are uneasy because they mistrust the new clientele who are competing for their status; and the artists themselves are unhappy, with many refusing even to show their faces at Art Basel “because it has nothing to do with art”.

Market reactions

Of course, this trade fair actually has a lot to do with art. But just not that exclusive, social arrangement where the participants used to set the price tag on a work of art. This is now endangered by the market itself, which is calling into question the very rules of the art world. Where exclusivity used to dominate, the market now wants to open up, and – like every market – it no longer makes concessions to any ‘passion’ for the thing in itself. Instead, all that counts is economic potency. It is this “reallocation of power relationships” that has caused the potential losers to turn against the big galleries, against the ‘nouveau riche’ and against the whole process of commercialisation.

These are the deeper-lying conflicts, and the sociologists are interpreting them by means of the social theories of Pierre Bourdieu. And behind this altercation in the name of ‘loving art’ there is indeed a competitive struggle going on among the ‘ruling classes’. At stake is the symbolic capital that art has long provided: its ability both to add beauty to our walls and to legitimise the societal position of its owners.

Art, says Franz Schultheis, is so valuable because it ennobles the art lover. And it’s still more than just merchandise. For this reason, it’s unlikely that the market will want to destroy its own magic. The question is rather who is going to control this magic in future.

Kunst und Kapital. Begegnungen auf der Art Basel. Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2015