For some, it's an up-hill battle

We are not all equal when it comes to viral infections. Some people end up out of action for weeks, whilst others recover spontaneously. Individual genetic variations may shed light on this phenomenon. By Marie-Christine Petit-Pierre

(From "Horizons" no. 108 March 2016)

Thanks to Angelina Jolie, everybody now knows about the mutations to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that cause breast cancers 1 and 2. We know that these mutations lead to a significant increase in the risk of both ovarian and breast cancer. This situation also illustrates the health impact of individual genetic variations.

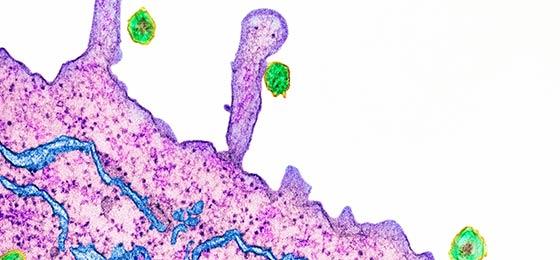

Our sensitivity to bacteria, viruses and fungi is also influenced by our genes. Pierre-Yves Bochud, a visiting doctor at the infectious diseases service of the Vaud University Hospital (CHUV), is working as part of a team tracking the influence of individual genetic variations on immune system responses in patients infected with certain microbes. In particular, they are looking at hepatitis C.

Avoiding ineffective treatment

A genetic variation in interferon-lambda (IFNL) 4 leads to a shortfall in the immune response, reducing the organism's capacity to fight against the virus, and even to respond to treatment correctly. "Whilst everybody produces the anti-viral protein IFNL 3, only a few people also produce IFNL 4". It should be a complementary weapon in the fight against the hepatitis C virus, but it's not. In fact, "it's as if the immune system burns out and runs itself into the ground, no longer capable of fighting the virus", says Bochud.

"Having detected the genetic variant means treatment regimes can be personalised, including in terms of their duration. For example, a person who doesn't produce IFNL 4 can have weeks cut from their prescription", he says. Having improved on previous efforts, the current treatment is effective in 90% of cases but it has also continued to be somewhat expensive at CHF 50,000 – 200,000 per patient. Now a quick screening test costing around CHF 100 helps decide which patients will receive treatment.

Genetic variations in IFNL 3 and 4 also play an important role in our defences against cytomegalovirus, an endogenous virus that leads to serious illnesses in immunosuppressed patients, such as those with advanced AIDS or with transplanted-organ rejection. "We can give a prophylaxis to risk patients", says Bochud.

Predicting risk

The same kind of mechanism is found in the gene PTX3, the variation of which leads patients to become more sensitive to pulmonary aspergillosis. This fungal infection can affect patients with leukaemia following intensive chemotherapy. In these cases, we can predict risk and improve the personalised management.

Jean Villard, head of the national reference laboratory for histocompatibility at the University Hospital Geneva (HUG), thinks that this research can also be applied to preventative medicine. When asked if we can envisage the correction of undesirable variants using genetic therapy, he says, "no, because it's generally clusters of genetic variations that are implicated. It's therefore very difficult, if not impossible to identify them all and then to establish the relations among them, some of which may protect us whereas others make us more vulnerable to certain diseases".

Marie-Christine Petit-Pierre is a freelance journalist.

A. Wójtowicz et al.: PTX3 polymorphisms and invasive mold infections after solid organ transplant. Clinical infectious diseases (2015)