"I'm frustrated"

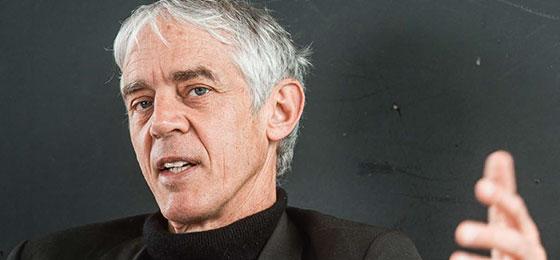

Martin Vetterli, President of the National Research Council of the SNSF, has been lobbying for open science for years. "You can't simply command it to happen", he says. As a researcher at EPFL, he discloses all his own raw data. By Atlant Bieri

(From "Horizons" no. 110 September 2016)

What does 'open science' mean to you as a researcher?

At the School of Computer and Communication Sciences at EPFL, we traditionally make all our published papers freely available online. We also provide all the associated data and source codes. In this manner, all our results can be reproduced by other research groups.

Researchers are already drowning in papers today. How can they hope to keep up if everything is going to be made freely available?

With open science, the exact opposite will happen. Publishing an article on this basis means that all data is documented clearly. Every step in our work that led to a result is described so that others can comprehend it. This means that, overall, fewer papers will be published, while their quality will rise at the same time. It will also make research more transparent.

How exactly do you go about this?

We still publish in the traditional journals. But even while we're submitting the paper, we put all our data on our server. As soon as the article is accepted, we also place it on free online access.

Shouldn't a researcher have the right to keep his laboratory recipes to himself?

Certainly not in my field, the computer sciences. And maybe the same should apply in other fields too. 350 years ago, we moved from the age of alchemy into chemistry. The alchemists simply claimed that they could produce gold according to a secret method. There was no possibility of checking their claims systematically. You could choose to believe them, or not. But all that changed with the onset of chemistry. We began to publish our methods. That was the moment when modern science was born. If we do things differently today, then we're returning to an age of alchemy.

Of all the publications that have resulted from SNSF funding, only 40 percent are freely available. As President of the Research Council, are you OK with that?

No. I'm frustrated. We are much too slow. Today, the Swiss taxpayers pay three times. First for the actual research, secondly for their subscription to the specialist journals where it's published, then thirdly for open access. This means the publisher profits twice. That's truly shameful. We can't tolerate it.

So what are you doing about it?

The SNSF is developing a strategy in tandem with Swissuniversities. We want to reach a point where all papers are available on open access, without our having to pay a further fee for them. We hope that we can conclude an agreement with the publishers so that researchers in Switzerland can get automatic open access.

How do you want to achieve this?

If Switzerland as a centre of research is able to present a united front, then we can go to the publishers and say: Either you do a deal with us now, or the Swiss research community will boycott you. That will be difficult, of course. But the Netherlands have managed it. And they've been successful.

Is Switzerland ready for such a step?

The whole situation is rather complicated. The many different researchers active in Switzerland have different interests. We're still finding it a little difficult to coordinate all these interests.

Couldn't the SNSF simply compel researchers to publish their data only in open-access journals?

That's not so simple, because in some cases it would be bad for their careers. Researchers have to endeavour to publish in journals that are best suited to their results. It's also our goal to further the careers of our researchers, not to hinder them.

Why doesn't EPFL found its own specialist journal?

A specialist journal of our own would be a very good idea. But it's not something that we can make happen on a top-down basis. It has to come from the research community itself. If a community decides to leave the traditional path, it will happen. But I'm not the person to decide that. Such a process would require a cultural shift among researchers.

Have researchers elsewhere already gone down that path?

Yes. Together with other researchers, the famous mathematician Timothy Gowers at the University of Cambridge has founded the journal 'Discrete Analysis'. It's a virtual journal. The editorial board can concentrate solely on peer-reviewing because the papers submitted are managed by an external company. The costs amount to about ten francs per manuscript. So it's a hundred to a thousand times cheaper than publishing in a traditional journal.

In 2012, an article in Nature showed that 47 of 53 important cancer studies were not reproducible. How is that possible?

To be fair, we have to admit that research is more difficult in some fields than in others. In medicine, for example, you only have a small amount of data because you're dealing with real people. That means that there are often problems with both statistics and reproducibility.

Nevertheless, the reproducibility crisis also affects other areas, such as biology, where you can choose your volume of data more freely.

I've heard well-known professors claim: "The other group couldn't reproduce that because they're not as good as us". There are indeed people who have a real knack – they can work with organisms so well that their experiments succeed, while others can't reproduce them. Nevertheless, I think that it's a weakness, because the goal of science is absolute reproducibility.

Isn't it just that people are cheating?

This can happen, but it's certainly not the norm. Here we also have to remember that researchers are in competition with each other. A bit too much competition today. The resulting pressure makes researchers feel compelled to publish their work, even when it's inadequate.

So is competition bad for research?

No, I wouldn't put it as simply as that. In science, we have always been keen to be the first to discover something. That's how we make progress in research, by being cleverer and better than the others. It's part and parcel of research that we compete against each other.

So what's the problem?

Today, it's particularly difficult for young people to become real researchers. Fifty years ago, we still had the leisure to think differently about the world and to generate new ideas. Today, research has become a business. The general public, politicians and the private sector think that you can pour money into research at one end, and get useful results out of the other end shortly afterwards. But of course it's not like that. Research needs time and space if people are going to be able to think creatively.

But researchers have it good at EPFL, don't they?

This is not just a Swiss matter. Research is global. And there are several alarming phenomena. In certain Asian countries, for example, researchers' wages depend on the specialist journals in which they publish. That's a dubious practice, because it almost encourages dishonest behaviour.

And does this have an impact on Switzerland as a centre of research?

Yes. Young researchers feel under pressure to publish. They'll turn the material for one article into three articles, because it looks better on their publication list. We also see this in requests for peer review. There's been a huge increase in recent years. The whole system is being swamped. And quality considerations naturally get left behind.

How can open science improve the current system?

If we shift to open science, then we'll produce fewer, but better-quality papers. And they can be reviewed quicker because everything is documented.

You're the next EPFL president. What concrete measures are you planning so as to promote open science there?

In those research fields that have already taken major steps into open science, I want to promote a research culture in which other fields are encouraged to join them. We're providing an online tool for this. It allows researchers to upload their data easily and let others see it. Third parties can then check it. But this tool is also intended to promote collaboration between different research fields. In the environmental sciences, for example, people aren't necessarily accustomed to dealing with large volumes of data. Here, the mathematicians or computer scientists could help them out.

How can you convince young researchers about the value of open science?

I tell them: The most important thing for your career is that your work has a big impact. If you place your data online, your work will become more visible and people will also trust you. And that will help your work to have a bigger impact. I can't compel them to embrace it. It's something they have to realise by themselves.

Atlant Bieri is a freelance science journalist.

Happy in the hot seat

Martin Vetterli is one of the pioneers of open science. He is a professor at the School of Computer and Communication Sciences at EPFL. He is also the President of the National Research Council of the SNSF until the end of 2016, and has been elected the new President of EPFL as of 2017.

For a better science

At the congress 'We Scientists Shape Science' on 26 and 27 January 2017, researchers and decision-makers together will take the first steps towards a creative, robust, committed science scene. This congress is being organised by the Swiss Academy of Sciences and the Swiss Science and Innovation Council.